The Dictionary of Spices

Chiles – No one is actually keeping score, but I bet if someone were, chiles would win as the New World’s most valuable contribution to world cuisine. The fruits of several species of the Capsicum genus have transformed the cooking of almost every region of the planet since Columbus delivered the first batch to his Spanish patrons at the close of the 15th century. (Although they are unrelated to the pepper that Europe was already familiar with, the Spanish called them pimiento (pepper) due to their pungency, and the name stuck.) It’s hard to imagine what many of the outstanding food cultures of the world were like before the introduction of what has become the world’s largest spice crop. What did the foods of India taste like before chiles? How did the people of Southeast Asia season their foods before chiles reached their shores? How did the Hungarians season their goulashes without paprika? What did the Spanish do before they had pimientos and their own smoky version of paprika called pimentón? What would Italian food be like without bell peppers or crushed red pepper flakes? Chiles are possibly the only spice that has so radically and permanently affected the cooking and eating habits of almost half the population of the planet.

Chiles get their “heat” from a compound called capsaicin which is most concentrated in the seeds and white membranes, with lower concentrations in the flesh of the fruits. The amount of capsaicin depends on the variety of chile as well as its ripeness, and experts agree that many other variables play a part in the ultimate spiciness of many varieties, including temperature, rainfall, and soil conditions. Ignoring this basic variability for a second, some chiles are spicier than others, as determined by the amount of capsaicin they contain. As a general rule, the larger, fleshier varieties are milder than the smaller, thinner-skinned varieties. Their “hotness” (it’s not actually heat, but rather a chemical stimulation of pain receptors in mucous membranes) is measured in Scoville units and ranges from zero Scoville units in the case of the mildest sweet bell peppers, to about 350,000 for the hottest habanero and Scotch bonnet varieties. It is said that capsaicin stimulates digestion and circulation, and it also provokes perspiration which accounts for the near-universal popularity of spicy foods in tropical climates.

With literally thousands of varieties under cultivation around the world, a comprehensive listing is far beyond the scope of this little article. However, this diversity points to the fact that Capsicum species are easy to grow just about anywhere, and the dedicated cook can have a personal crop of chiles growing in the backyard or in pots on window sills virtually anywhere in the world. Usually classified as annuals, chiles are easily grown from seed and will bear fruit in their first season. If you happen across a fresh or dried chile you are particularly fond of, try saving some of the seeds and planting them in the spring. You will almost certainly be rewarded with your first crop in a matter of weeks, although the fruits may not be identical to the parent due to cross-pollination.

When fresh, they have a characteristically smooth and shiny skin in vibrant colors ranging from green to yellow, orange, fire engine red, and deep maroon, and may be eaten at any stage of maturity. They may be dried or frozen, although freezing will result in a loss of flavor and spiciness unless they are blanched first. In their dried form the flavor is concentrated and, ounce for ounce, the spiciness may increase as much as tenfold. Dried chiles will keep almost indefinitely in an airtight container.

The uses of chiles are almost too numerous to mention. They are used fresh and dried, whole, chopped, and ground, raw, pickled, and cooked in sauces, pastes, oils, preserves, and powders. They come in various guises and are marketed under various names: cayenne pepper is the pulverized form of the dried red cayenne chile; paprika is the dried and pulverized form of sweet and mildly spicy red chiles; chile powder is a mixture of powdered chiles (often ancho chiles) with other herbs and spices such as oregano and garlic; hot sauces are made by preserving chiles in brine or vinegar; chile oils are made by steeping chiles in oil for a period of time; pimientos are the preserved flesh of red chiles similar to bell peppers; and hot pepper flakes are the dried, crushed form of any of a variety of spicy red chiles.

The flavors range from mild to infernally hot, as we have already seen, but the flavor spectrum is not limited to degrees of spiciness. Different types of chiles are valued for their different flavor components everywhere chiles are used. Some are fresh and “green” (it’s a chlorophyll thing) in flavor while others can be slightly bitter (especially yellow chilies) to sweet with overtones of raisins, prunes, and chocolate. Some attack the tongue with their chemical assault, while others gently stimulate the back of the throat. Cooks in Central and South America and the Caribbean have been keenly aware of these differences for thousands of years and it is not uncommon for some traditional preparations to call for three, four, or even more types of chiles in order to form a combination of flavors from what each variety of chile provides.

Yes, the flavors can be overwhelming (especially to the uninitiated), but they can also be exceedingly subtle as well. Chiles get my vote for the most important spice of all time.

Cinnamon – The dried bark of the Cinnamomum zelanicum tree native to Sri Lanka, true cinnamon is more subtle in flavor than cassia, but it also has a hint of cloves from the oil eugenol which cassia lacks. As with cassia, its primary use in the West is in sweets and baked goods, but it is also used in savory meat and vegetable dishes in North Africa, the Middle East, India, China, and Latin America. In Mexico it is traditionally combined with chocolate, and in India it is a component of many masalas, chutneys, and other condiments. It is available as sticks (aka quills) and in ground form. When ground it loses its potency quickly, so buy it in small quantities. In stick form it will retain its flavor for several years.

Citrus – The juice and the pickled, preserved, fresh, or dried rind of many members of the Citrus genus give an unmistakable citrus flavor and aroma to any dish they touch. In North Africa whole lemons are preserved in salt so the pickled rind can be used in chicken, lamb, and couscous dishes. Whole dried limes are added to stews and pilafs in the Middle East. The Japanese use the dried rind of yuzu, an indigenous citrus whose flavor is similar to a cross between a lemon and a lime, in soups, simmered dishes, condiments, and sweets. In the West we use the juice, rinds, and zest (the outer colored part of the skin) to flavor baked goods, desserts, and candies, and in the Caribbean and Latin America the juice is used in innumerable marinades, ceviches, and mojos. And let’s not forget all the beverages that citrus fruits have contributed their juice to all over the world. Candied and dried citrus rinds will keep indefinitely.

Cloves – The dried, unopened flower buds of Syzyium aromaticum, a small tropical evergreen tree native to the Moluccas in Indonesia, were known to ancient Romans thanks to an overland trade in spices dating back thousands of years. Eugenol is the essential oil that gives cloves their unique flavor which is appreciated in virtually all parts of the world. The taste can be overpowering if used indiscriminately, and excessive amounts will actually produce a mouth-numbing sensation. They are used in sweet and savory dishes in the Middle East, North Africa, India, China, and Southeast Asia. In Europe and North America they are often included in pickling mixtures, spiced breads, and ham dishes. In India they are one of the basic ingredients of garam masala, in China they are essential to the five-spice mixture, and in France they are one of the four spices in quatre epices (along with black pepper, nutmeg, and dried ginger). In Indonesia they are mixed with tobacco and made into the aromatic kretek cigarettes. Ground cloves lose their flavor quickly, so buy in small quantities or buy the whole cloves which will retain their flavor for at least a year if properly stored.

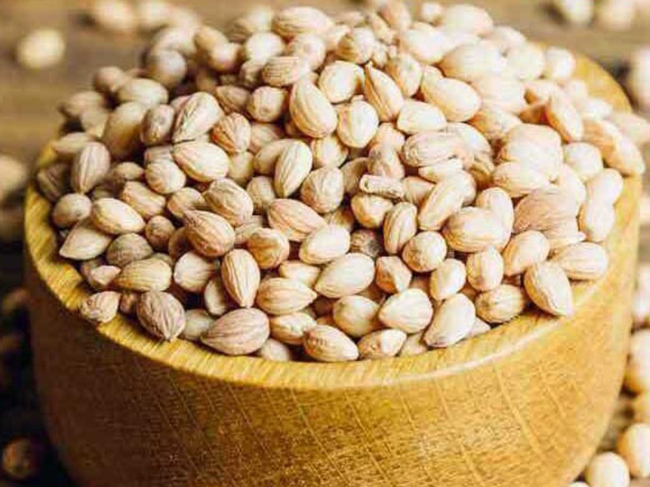

Coriander seeds – The dried seeds of the Cariandrum sativum plant, which also gives us the herb cilantro, have a sweet, spicy fragrance with hints of pepper and orange peel. They are widely used throughout North Africa, the Middle East, and India as a flavoring for meat and vegetable dishes, stews, and sausages. In Europe and North America they are usually found in pickling spice mixtures and in cakes and cookies. The whole seeds are easily crushed or ground and retain their flavor much longer than the pre-ground form available on the market.

Cubeb – The dried immature fruits of a tropical vine (Piper cubeba), cubebs are a close relative to black pepper which they resemble in appearance and flavor. Cubebs also have notes of allspice and a strong, pine-like pungency that mellows in cooking. Also known as Java pepper, they were popular in Europe from the 16th to the 18th centuries as a substitute for black pepper, and are scarcely known outside of Indonesia today. They are enjoying a minor resurgence in popularity among spice aficionados and are sometimes available from specialty spice shops.

Cumin – The dried seeds of the Cuminum cyminum plant, a small umbellifer related to caraway, dill, and fennel, are possibly my all-around favorite spice. Judging from its long history and ubiquitous nature, it’s one of the world’s favorite spices as well. Native only to the Nile valley in Egypt, the spice has been used in the Mediterranean, North Africa, India, and China for at least 4,000 years. Ancient Egyptians and Minoans used it for medicinal purposes, and the Romans used it much the way we use pepper today. Its unique and indescribable flavor is used to season every type of food, from cheeses in Holland and pickled cabbage in Germany to fish dishes in Lebanon, couscous in Morocco, and tapas in Spain. Many dishes from India and Mexico would be unrecognizable if the cumin were omitted—a garam masala or chili con carne wouldn’t be the same without it. As with all seeds used as spices, cumin benefits from heating; the flavor is enhanced by dry roasting before grinding, or by frying in hot oil if being used whole.

Dill seeds – The seeds of another umbellifer, both the leaves and seeds of Anethum graveolens are used in cooking, making it one of the few plants that provides us with both a spice and an herb. The seeds have a flavor reminiscent of caraway anise, with a touch of citrus. They are what puts the “dill” in dill pickles, and are used in many Scandinavian and Norther European baked goods. Dill is easily grown and will self-seed readily. Harvest the seed heads when they are fully formed and dark brown. Place them in a paper bag and allow to dry in a warm place. When they are dry, rub the seedheads between your hands to separate the seeds from the husks. Whole seeds will remain fresh for at least two years if stored in an airtight container.

Fennel seeds – Yet another umbellifer, the dried seeds of Foeniculum vulgare are used to season pickles, breads, sauerkraut, and cured as well as fresh sausages. With its anise-like flavor, it is one of the components of Chinese five-spice powder and Indian garam masala. It is easily grown and can be harvested like dill seed (see above), however, dill and fennel plants should not be grown in close proximity to each other because they will cross-breed and produce hybrids. Fennel pollen imported from Italy, which has an intense flavor even when used in small quantities, has been a recent fad among foodies, and this trend may have already passed.

Fenugreek – The dried seeds of Trigonella foenum-graecum are widely used in Middle Eastern, North African, and Indian cooking, but never seem to have caught on in the West. The “foenum-graecum” part of the name means “Greek hay,” referring to the plant’s widespread use as animal fodder in classical times. The seeds have a strong flavor reminiscent of celery or lovage, and it is the dominant flavor in some curry powders. In India it is used in pickles and chutneys; in North Africa it is often added to breads, and in Turkey it is used to cure dried beef. Dry-roasting or frying brings out a nutty, burnt sugar or maple syrup flavor.

Galangal – The rhizome of a couple of Alpinia species, galangal can be used fresh or dried. With a flavor similar to its cousin ginger, it is used in a similar manner in the cooking of southern China and Southeast Asia and is sometimes called Laos, Siamese, or Thai ginger. It is an essential flavor component in Thai curries. You may substitute ginger in recipes calling for galangal if it is not available in your area.

Garlic – Perhaps the most widely used spice in the world, the bulbs of Allium sativum have been cultivated in central Asia and the Middle East for thousands of years. It was originally used in medical and magical potions, but the ancient Egyptians discovered its benefits in the kitchen and began growing it on a large scale. It is available in many forms, including fresh heads of garlic, dried garlic flakes and powder, garlic salt, extract, and juice. While some of these products may offer something in terms of convenience, they all lack the flavor of true, fresh garlic, and should only be used when fresh garlic is unavailable.

In addition to Allium sativum (which we consider to be basic, regular old garlic), several other related species are also used around the world. The most familiar to Americans is probably the bulb of A. ampeloprasum, which is actually a type of leek and is marketed as “elephant garlic.” The cloves of this plant may weigh up to an ounce (28 g) each, and although they are too mild to replace true garlic in cooking, the whole cloves are good roasted with other vegetables. Similarly, wild members of the genus are often collected and used as garlic. In southern Europe rocambole (A. sativum var. ophioscorodon) and ramsons (A. ursinum) are often cultivated and sold in markets, while aficionados of wild American garlic (A. canadense) and wild onions (or ramps, A. tricoccum) will most likely have to collect their own.

The characteristic odor of garlic (as with the other members of the onion family) is formed when enzymes and other compounds come into contact with each other as a result of the crushing, slicing, or chopping of the garlic, and this chemical activity results in the production of several disulphate compounds which owe their pungency to the sulfur compounds they contain. In other words, the more finely garlic is chopped, the more pungent it becomes. This accounts for why some recipes would have you mash the garlic to a pulp (as in aioli and pesto Genovese) for the maximum garlic flavor, and others require a more restrained chopping, slicing, and even leaving the garlic cloves whole in order to moderate the flavor. When garlic is heated the disulphate molecules are rearranged to form different, less pungent disulphates, which is why garlic and its cousins lose so much of their punch when cooked.

The same disulphate compounds that give garlic and the other members of the Allium genus their characteristic flavor are also, as you might expect, responsible for the lingering aroma on the hands and breath of those who have cooked with and eaten it. Unfortunately, modern science has little to offer to remedy the noxious breath (and occasionally even body odor) that accompanies the consumption of garlic, but there is a surefire way to eliminate the odor from your hands. Don’t ask me how this works because none of my scientific food resources contain any mention of it, but I have tested this procedure and it’s the real deal: after cutting garlic or any other member of the onion family, run water over your fingertips as you rub them on a piece of stainless steel. You may use a spoon, fork, or even the bottom of the sink if it is stainless steel, and they even sell little pieces of stainless steel for this purpose. Try it—you’ll be amazed.

Ginger – The fibrous rhizome of the Zingiber officinale plant, native to China and Southeast Asia, is used in sweet as well as savory foods nearly everywhere in the world. Fresh ginger (also known as gingerroot) has a sharp, pungent flavor with sweet, citrus undertones. It is used throughout Asia in every type of dish. In Europe and the rest of the Western world, ginger is more likely to be used in a dried, candied, or preserved form because it was in these forms that ginger was traded from the Far East for many centuries.

Fresh ginger may be used sliced, minced, grated, or added whole to a dish and removed before serving. Even though it is not necessary to peel fresh ginger, the thin brown skin is easily removed by rubbing with the edge of a spoon.

When buying fresh ginger, look for pieces (called “hands” in the trade) that are hard, unwrinkled, and heavy for their size. It will keep for up to three weeks in the refrigerator, and almost indefinitely frozen. Store some fresh ginger in a small glass jar filled with dry sherry in the refrigerator. This will provide you not only with fresh ginger that will keep for several months, but the ginger-flavored sherry can also be used in cooking, and you can refill the jar with both sherry and ginger to maintain your supply.

Dried, powdered ginger is most often found in baked goods in the West. Its flavor ranges from peppery and lemony in the case of the better grades, to sharp and bitter in the case of the less expensive grades—buy Jamaican or Cochin ginger if possible. It is also widely used in Asia, especially in spice mixtures such as Chinese five-spice, masalas, and curries. Crystallized ginger may be eaten as is, or used to flavor baked goods, ice cream, and cakes. Ginger is often pickled in vinegar and served as a condiment, especially in Japan where one method produces gari, the paper-thin slices of ginger (made pink by the pickling) that accompany sushi.

Grains of Paradise – The seeds of the Amomum melegueta plant, a relative of the plant that gives us cardamom. Native to Western Africa, grains of paradise are also known as Guinea pepper, Melegueta pepper, and occasionally alligator pepper. The spice was once popular throughout Europe as a replacement for the more expensive true pepper, but as the supply of true pepper grew over the centuries, so the demand for grains of paradise diminished. It is still used in Scandinavia to flavor aquavit, and continues to be one of the essential spices in African spice mixtures such as qalat daqqa and ras el hanout.

Horseradish – Although the leaves may be added raw to salads, it is the root of the Armoracia rusticana plant that most people are familiar with. It figures prominently in the cooking of its native region of eastern Europe and western Asia where it still grows wild. Its culinary history probably began in Russia and the Ukraine, and spread to Scandinavia, Germany and the rest of Europe through the Middle Ages. The freshly grated root is extremely pungent enough to make your eyes sting and nose run, and vinegar or lemon juice are added to enable an enzymatic reaction that produces the sharp, peppery flavor we are familiar with. Traditionally served to accompany roast beef in the British Isles, tongue in Germany, and boiled beef in Austria and elsewhere, fresh horseradish will keep for several weeks in the refrigerator, and for more than a year in the freezer.

Juniper Berries – The dried berries of the common juniper plant (Juniperus communis) used in landscaping are probably best known as the dominant flavor in gin. In fact, our word for gin is derived from genievre, the French word for juniper. They are widely used throughout Europe, especially with wild game dishes where their powerful, woodsy, pine-like flavor will not overpower the meat. They are used to flavor sauerkraut in Alsace, in pickling mixtures in Scandinavia, and pates in France. Pick the ripe blue-black berries from juniper plants that have not been treated with chemicals and dry them for home use. The berries take two years to ripen, so both ripe and unripe green berries will appear on the same bush.

Kokum – Since the Garcinia indica tree is native to and grows almost exclusively in India, it’s no surprise that the fruit is used primarily in Indian cooking. The whole dried fruit and the dried rind have a slightly fruity, sour taste and are used much like tamarind to add a mildly tart note to beverages, sherbets, and condiments.

Licorice – The roots of several species of the genus Glycyrrhiza, perennial shrubs native to Europe and Asia, are used to flavor baked goods, candies, liqueurs, and soft drinks. They may be eaten (chewed, actually) raw, but are most often sold in dried and powdered form. The plants are easily grown from seed or root cuttings, and the roots may be harvested in the fall and will take several months to dry. The majority of the world harvest is used to flavor tobacco, and cough syrups and other medications rely on its powerful flavor to mask medicinal tastes.

Mace – This is going to take a little explaining. You see, the Myristica fragrans tree of Southeast Asia produces a fruit that resembles an apricot. The large, hard seed in the middle of the fruit is the spice we know as nutmeg, and it is surrounded by a lacy, orange-red covering called an aril. This is mace. Although it is most commonly found in ground form, the dried arils are sometimes available and are worth seeking out because they have an almost indefinite shelf life when properly stored, and can be ground in a pepper grinder or spice mill. The flavor is very similar to nutmeg, with hints of pepper and cloves. In China and Southeast Asia its primary use is medicinal, and in the West it is used primarily in baked goods and pickling mixtures, where it can be used interchangeably with nutmeg.

Mahleb – Also known as mahlab and mahaleb, the kernels of a sour cherry Prunus mahaleb are used primarily in baked goods in the Middle East. The soft kernels are removed from the center of the cherry pits and dried before they are used whole or in ground form. They have a flavor reminiscent of cherries and almonds.

Mastic – The dried resin of a member of the cherry family, Pistacia lentiscus. It has a light, pine-like aroma and taste. It is usually sold in a form known as “tears,” small nuggets of the dried resin which is always ground to a fine powder before being used. It flavors many breads, cheese pastries, puddings, and preserves and is widely used in the Middle East and is not widely available elsewhere. It is brittle and easily crushed, and takes on the consistency of chewing gum when chewed and so has been popular as a breath freshener for centuries.

Mountain Pepper – The fresh and dried berries of Tasmannia lanceolata, a small shrub native to Australia, it is often used as a substitute for pepper in combination with other Australian bush spices. The small, dark berries resemble pepper in appearance, and can be ground in a pepper mill. The berries are very potent with an intensive bite more pungent than pepper, and may even provide a mouth-numbing effect if used to excess.

Mustard – The dried seeds of several members of the Brassica genus are valued worldwide for their pungent flavor. In Western cooking the whole seeds are a common ingredient in pickling mixtures, but the vast majority of the mustard we consume is in the form of prepared mustards. These run the complete spectrum from smooth and mild to coarse and fiery hot, depending on the type of mustard seed used, whether they are used whole, crushed, or finely ground, whether the husks were removed in the processing, and the liquid they are combined with. The spiciness of prepared mustards is provided by an enzyme called myrosinase which is activated by water, and the ultimate flavor of prepared mustard is determined largely by the liquid used: vinegar gives a mild mustard, white wine gives a sharper version, beer produces a fiery hot mixture, and pure water provides the hottest mustard of all. The bright yellow stuff often called “ball park” mustard

is more properly known as American mustard and is characterized by the addition of entirely too much turmeric, which accounts for its bright color, dusty taste, and finger-staining ability. Prepared mustards are also flavored with a variety of other ingredients, including honey, herbs, fruit extracts, and other spices. Mustard loses its potency when heated, so is best added at the table or during the last stages of cooking. Whole mustard seeds will retain their potency and flavor for at least a year when stored properly, but ground mustard loses both after a few weeks.

Nutmeg – The kernel of the seed of the Myristica fragrans tree of Southeast Asia, the same plant that also provides us with mace. With a taste similar to mace but with overtones of cloves, nutmeg is relatively inexpensive compared to mace because the yield of nutmeg from a given tree is about ten times that of mace. It is added to just about every form of preparation, from breads and baked goods to vegetable dishes (it is a classic seasoning for fresh spinach), stews, meat fillings for pastas and pastries, and many fruit, egg, and cheese dishes. It is also an essential ingredient to many spice mixtures used throughout Europe, north Africa, and the Middle East, and it’s hard to imagine a good old American pumpkin pie without it. Whole kernels of nutmeg last indefinitely, while the ground product quickly loses its flavor. Consumed in large quantities, nutmeg has hallucinogenic properties and can be toxic and even fatal if consumed in excessive quantities.

Nigella – The seeds of the Nigella sativa plant, better known to gardeners as love-in-a-mist, native to southern Europe and western Asia, are used primarily in the cooking of India. They are ground and added to legume and vegetable dishes, curries, pilafs, chutneys, and pickles in India, and are used whole as a pickling spice in Iran and other parts of the Middle East. The aroma is reminiscent of mild oregano, and the flavor is mildly peppery with nutty, earthy overtones. Available in Indian and Middle Eastern specialty shops, always buy whole seeds because the ground form doesn’t last as long and may have been adulterated with less expensive ingredients.

Pepper – When history books refer to the spice trade, what they are really talking about is the pepper trade. Pepper originally reached Europe over 3,000 years ago, and our craving for it has never diminished. It has been used as currency, exchanged ounce for ounce with gold, and used to pay ransoms, taxes, and dowries.

Today, the fruits of the Piper nigrum vine are the world’s largest spice crop in both volume and value. Native to India, they are now grown commercially in Indonesia, Brazil, Vietnam, and Malaysia as well. Pepper owes its bite to an alkaloid called piperine, and its warm, woody, sometimes citrus-like flavor is derived from several essential oils. The balance of these essential oils and piperine vary according to the origin of the pepper: Indian Malabar pepper is reputedly the best with its

balanced blend of bite and aroma; Indonesian lampong pepper has more bite and less aroma; Malaysian Sarawak pepper has even less aroma; and Brazilian and Vietnamese peppers generally contain less piperine, making them less pungent.

Of the several forms of pepper available to modern cooks, black pepper is by far the most common. It is produced by picking the berries when they are still green, fermenting them briefly, and then drying them. In the course of fermenting and drying, the berries shrink and the skin becomes black or dark brown and wrinkled. The skin is where many of the essential oils are located, giving black pepper its unique and complex aroma and flavor.

White pepper is the inner core of berries that have been picked when they are yellow-orange and almost ripe. They are soaked briefly to soften the outer skin, which is then removed. Without this outer skin and its resident oils, white pepper is almost without aroma, and with only piperine to provide the bite, its flavor is considered flat and uninteresting by many. It is often used in cream sauces in order to avoid the visible black specks that black pepper would provide. The best white pepper is said to be Muntok from Indonesia.

Green peppercorns are picked green and freeze-fried or pickled in brine or vinegar. They have less bite than other forms and add an agreeable fresh note. Red peppercorns (not to be confused with pink pepper) are picked ripe and treated the same as green peppercorns. They have a delicate sweet, fruity taste, but are not widely available outside of Southeast Asia.

The uses for pepper are too numerous to list here because it is used in just about everything, just about everywhere. If you have bought ground black or white pepper, go to the kitchen and throw it away right now. Regardless of how recently you bought it, it has already lost most of the essential oils that provide its flavor, and all you have left is what amounts to dried sawdust with a splash of piperine. Whether you are buying black, white, green, or red pepper, buy whole peppercorns only. They will retain their flavor for over a year (longer if frozen), and a couple of grinds of a pepper mill will remind you what pepper is supposed to taste like.

Pink Pepper – The dried berries of the Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius) should not be confused with the fruit of the Piper nigrum vine. Although pink peppercorns have small amounts of the alkaloid piperine that gives true pepper its bite, the two plants are unrelated. The berries are available dried or pickled in brine or vinegar, and have a pleasant, fruity taste with hints of pine and juniper. Even though the plant is native to Brazil and southern South America, it has naturalized in California and Florida as well as many parts of the Mediterranean due to its popularity as a landscape plant. Pink pepper is grown commercially only on the French island of Reunion in the Indian Ocean, and imported through France which helps to account for its exorbitant price. There have been reports of gastric and respiratory irritation associated with the consumption of pink pepper, especially with regard to the berries found growing wild in Florida. The berries grown on Reunion seem to be free of the irritant and have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. As with all peppers, buy whole peppercorns and crush or grind them immediately prior to using them.

Pomegranate – Both the seeds and the juice of the fruit of the Punica granatum tree native to the Middle East and southern Asia add a sweet-tart taste to salads, stews, curries, chutneys, baked goods, and desserts in India and the Middle East. The dried seeds, known as anardana in India, add a crunchiness in addition to their fruity taste. The juice may be drunk as a beverage or added to sauces. Pomegranate molasses made from the juice is currently in vogue with trend-following chefs who add it to sauces, gravies, and salad dressings.

Poppy Seed – The protein-rich seeds of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum, or “sleep-inducing poppy”) are used primarily in baked goods in the West. They are often sprinkled over breads and sweet buns, and ground into a paste as a filling for pastries. In India they are frequently ground and added to spice mixtures for kormas and curries and used in vegetable dishes. They range in color from almost black to slate-blue, pale brown, and cream-colored. Their subtle flavor and aroma are reminiscent of almonds and are enhanced by dry-roasting or baking. Because of their high oil content they tend to go rancid quickly, so buy them in small quantities and store them in the freezer. Although they contain none of the narcotic properties of the milky sap of the plant that is used to make opium, it is no urban legend that the consumption of poppy seeds can provide a false positive reaction for opiates in drug screenings.

Rose – Westerners don’t usually think of roses as a flavoring for foods, but the dried buds and petals of the most fragrant members of the Rosa genus are used widely throughout north Africa, the Middle East, and India. Although the dried and ground petals are used in marinades and stews in India and north Africa, the most widely used form of rose flavoring is rose water made with the distilled essence (attar) of roses. This is used in all types of dishes, especially in beverages and sweets. Its contribution to a dish is primarily aromatic when used in moderation because the pungent, medicinal flavor can be overpowering. Rose is available as dried petals and buds, rose water, rose oil, and rose petal preserves in Middle Eastern and Indian specialty shops.

Safflower – Although we know it better for the oil extracted from its seeds, the dried flowers of the thistle-like plant Carthamus tinctorius are also valued, primarily for their ability to color foods yellow. In fact, unscrupulous spice merchants may try to pass it off as the much more expensive saffron, and it is often called false saffron. It is almost without aroma, and has a subtle bitter and lightly pungent flavor. It is used to color rice, stews, soups, and sauces in India, Portugal, and Turkey.

Saffron – The stigmas of a wild crocus (Crocus sativus) native to the Mediterranean and western Asia are, pound for pound, the most expensive spice in the world. The stigmas of more than four thousand blooms must be plucked by hand in order to produce a mere ounce (28 g) of the spice. Saffron lends a yellow color and a musty, floral aroma to dishes it is used in, but caution should be used because more than a pinch will yield a bitter, medicinal taste. It is widely used around the world to color and season risottos, pilafs, paellas, and many other traditional rice dishes, and is also an essential ingredient in such fish soups as the French bouillabaisse and the Catalan zarzuela. The Swedes add it to buns and cakes to celebrate Saint Lucia’s day in December, and traditional saffron cakes are still available in Cornwall. Saffron is available as dried stamens (known as threads) and in powdered form; buy threads if possible because the ground saffron is easily adulterated with less expensive ingredients. For best results, lightly toast the threads before adding them whole or crushed to a dish, or steep them in warm liquid for 5 minutes to make an infusion.

Sesame seeds – The Sesamum orientale plant has been cultivated for its seeds for at least three thousand years. The small seeds range in color from ivory to red, brown, pale gold, and black, and are used in the West primarily as a topping for baked goods. In India, Asia, and the Middle East they are often used to add flavor and texture to seafood, chicken, noodle, and vegetable dishes. They are the primary ingredient is such sweets as Middle Eastern halvah and Indian til laddoos. Whole, raw seeds are ground into the paste tahini which is used to make hummus, baba ghanoush, and many traditional Middle Easter dishes. Asian sesame oil, used widely in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean primarily as a seasoning rather than a cooking oil because of its low smoke point, is made from toasted seeds and provides a distinctive, nutty flavor. Because of their high oil content sesame seeds tend to go rancid quickly, so buy them in small quantities, store them in an airtight container in the freezer, and toast them as needed.

Star Anise – The dried fruit of the Illicium verum tree, a type of magnolia native to China and Japan, definitely takes the prize as the most attractive spice with its star-shaped seed pods. It is an essential ingredient in Chinese five-spice powder as well as many Chinese soups, marinades, and braising liquids, and Vietnamese pho (beef and noodle soup) wouldn’t be right without it. It has a sweet, warm flavor with notes of anise, fennel, and licorice, and is used in the West primarily as a flavoring ingredient in liqueurs such as pastis and anisette, and in chewing gum and pastries. Although it is sometimes available in ground form, buy only the whole pods and add them whole to soups and stews (remove them before serving), or grind them yourself in a spice mill.

Sumac – The dried berries of a shrub (Rhus coriaria) native to Iran and the Middle East are used to add an acidic note to dishes much the way lemon juice is used in the West and tamarind is used in Asia. The berries may be used whole, powdered, or to form an infusion. Sumac is a frequently used ingredient in the cooking of Turkey, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria where it is used to flavor beverages, breads, fish, chicken, and vegetable dishes. It is also served in its crushed or powdered form as a condiment with kebabs.

Szechwan pepper – The dried berries of the Zanthoxylum genus of prickly ash trees native to China (Z. simulans) and Japan (Z. piperitum) are an essential ingredient in Chinese five-spice powder and Japanese seven-spice mixture. They have a fragrant, woodsy, peppery flavor with hints of citrus and are used in all manner of meat, poultry, fish, and vegetable dishes. They are currently banned from importation into the United States because they are a vector for a disease that attacks native ash trees.

Galangal – The rhizome of a couple of Alpinia species, galangal can be used fresh or dried. With a flavor similar to its cousin ginger, it is used in a similar manner in the cooking of southern China and Southeast Asia and is sometimes called Laos, Siamese, or Thai ginger. It is an essential flavor component in Thai curries. You may substitute ginger in recipes calling for galangal if it is not available in your area.

Tamarind – The reddish-brown pulp that surrounds the seeds inside the seed pods of the Tamarindus indica tree of Madagascar and eastern Africa is the only spice of importance to have originated on the African continent. The pulp is often formed into cakes or blocks which are typically soaked in water to form a tart infusion which is added to dishes, and it is also available as a concentrate (or syrup) and paste. It is used in a wide variety of dishes whenever an acidic note is desired, and is one of the predominant flavors in Worcestershire sauce. It is used in all types of meat and vegetable dishes in China, Southeast Asia, and India, and as a flavoring for beverages in the Caribbean and Latin America.

Turmeric – The fresh or ground rhizome of Curcurma longa, a plant related to ginger, adds a bright yellow-orange color and subtle flavor reminiscent of ginger and citrus to many sweet and savory dishes. The world’s largest producer is India, the majority of whose crop is used domestically. One of the world’s least expensive spices, it is also grown commercially in China, Haiti, Jamaica, Peru, and several Southeast Asian countries. It is an essential ingredient in many Indian curries and masalas and contributes the distinctive yellow color to those dishes. In the West is it most frequently used as a coloring agent in cheeses, margarine, mustards, and pickling mixtures. Fresh rhizomes are widely available throughout Asia, but the most common form of the spice in the West is the powdered form. The fresh rhizomes freeze well and may be stored for several months in an airtight container in the freezer. The powdered form will retain most of its flavor and all of its coloring ability for more than a year when properly stored.

Vanilla – It’s ironic that among the orchid family of plants, the most numerous and geographically widespread family of plants on the planet, only one offers a food product. The seed pods of the climbing perennial orchid Vanilla planifolia native to Central America have no flavor or aroma when they are picked. They are parboiled, sun-dried, and fermented in a lengthy and complicated process during which the pods shrivel, darken, and develop aromatic compounds, the most recognizable of which is vanillin. Today vanilla is grown commercially in Mexico, Reunion, Madagascar, Tahiti, and Indonesia, and although each claims superiority over the others, I doubt that even the most sensitive palate would be able to distinguish them. It is available in most supermarkets in two forms: whole “beans” (the commercial designation for the seed pods); and as an extract made by macerating the pods in alcohol.

The Aztecs introduced their Spanish conquerors to vanilla as an ingredient in the chocolate beverage served in the court of Moctezuma, and the Spanish returned to Spain with both chocolate and vanilla. It is still used widely for its original purpose in the manufacture of chocolates and other sweets, as well as in the full spectrum of baked goods, ice creams, and sweet treats the world over. The beans may be used whole to infuse sauces and syrups, after which they may be rinsed, dried, and reused. Added whole to sugar, they will impart their unique flavor to the sugar for use in baking or for sweetening a cup of coffee or tea. The beans may also be split and the tiny black seeds may be scraped out of the pod prior to being added to a dish. Although its primary use is to flavor sweet preparations, vanilla also goes well with seafood (especially lobster, scallops, and mussels) and is also added to black beans in Mexico.

When buying vanilla extract, be sure to look for “pure vanilla extract” on the label, and when buying whole dried beans, try to buy those with a light dusting of white crystals of vanillin on the surface. Vanilla beans will retain their flavor for up to two years if properly stored, and vanilla extract will last indefinitely.

Wasabi – The root of the Eutrema wasabi plant native to Japan is frequently called Japanese horseradish even though the two plants are not related. In Japan the root is available fresh and is often grated and added to fish dishes, but the rest of the world has to be content with powdered wasabi, or with powdered wasabi that has been prepared in a paste. In its dry, powdered form wasabi has little taste and only develops its eye-tearing and sinus-clearing pungency when mixed with water. It loses its flavor when exposed to heat, so is typically served with and added to cold foods. It is essential to sashimi and sushi. When buying powdered wasabi, read the label carefully. Many so-called “wasabi” products actually contain horseradish, mustard, and food coloring because wasabi is expensive to grow due to its finicky horticultural requirements. The real thing should cost at least twice as much as the imitation. Powdered wasabi has a shelf life of several months, and the prepared paste will last almost as long if properly stored.

Wattle – Of the thousands of varieties of acacia trees in the world, only a few have edible seeds. The Acacia victoriae and A. aneura are among the Australian species that are valued for their seeds. Their flavor has been likened to coffee, hazelnuts, and chocolate, and they are used in custards, ice cream, cheesecakes, and other baked goods. Wattle seeds are expensive because they are collected in the wild and require a labor-intensive process to make them ready for market, and because their demand exceeds their supply. They are available in Australian gourmet markets and specialty spice shops, but have failed to make much of an impact on the rest of the world.

Zedoary – The rhizomes of several members of the Curcuma genus are used in Southeast Asia in a manner similar to ginger and galangal, two close relatives. Although it has been known to Europeans for at least 1,500 years, its use has been primarily as a medicinal herb in the West. Nowadays its culinary use is limited mainly to Southeast Asia, but it is becoming increasingly available in Asian markets around the world. Sometimes called “white turmeric,” the fresh rhizomes may be grated, chopped, or sliced and used like ginger. Dried zedoary is rarely found outside Southeast Asia.